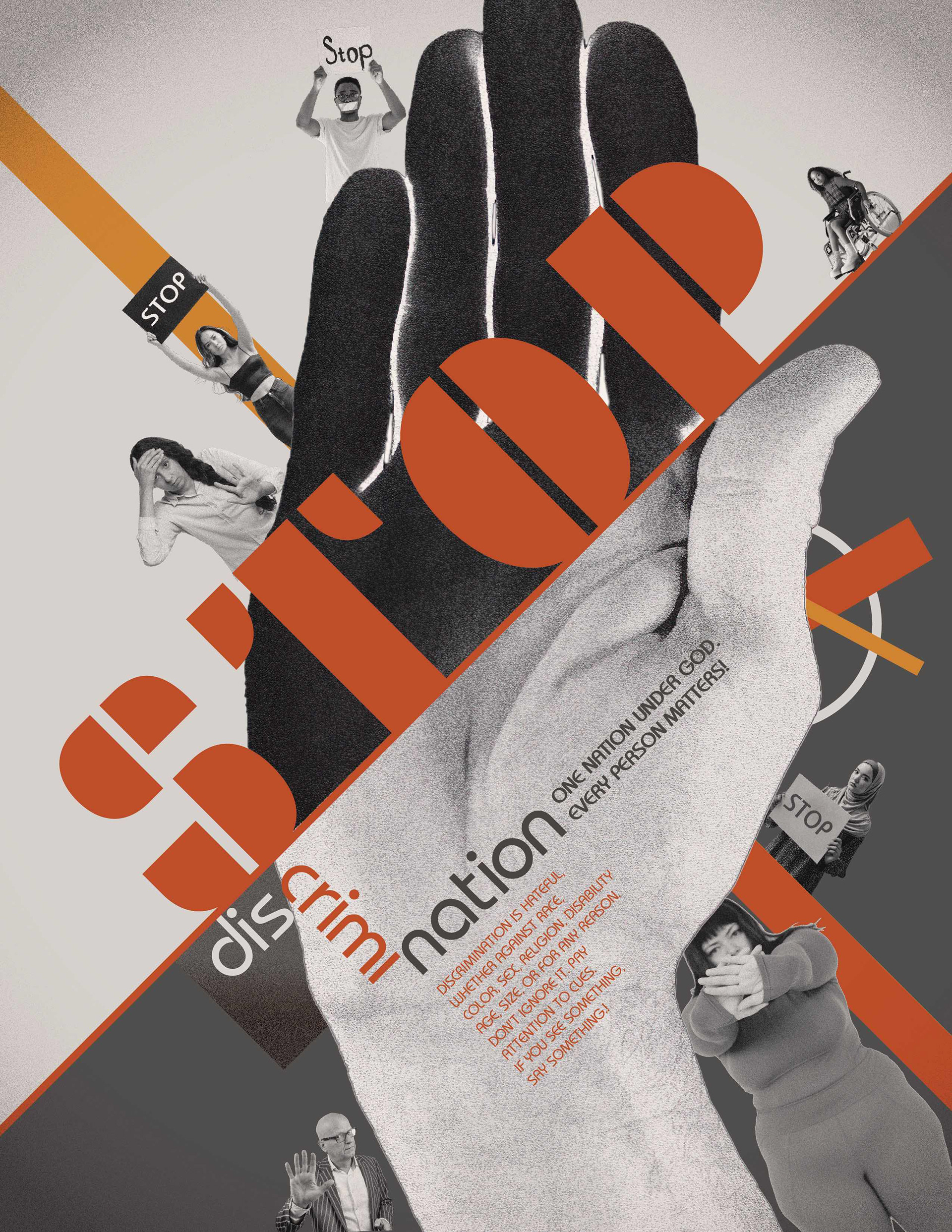

STOP DISCRIMINATION

Poster & Billboard Social Campaign Design, Research & Essay

Style Inspired by the 1925's

German Bauhaus Design School and artist Lazlo Maholy-Nagy

Work Process

Artwork on Adobe Illustrator

Photography Stock images (Pexel.com)

Research

Moholy-Nagy: Art Lawyer that Saved the Bauhaus

Firas Otabachi, Essay

History of Graphic Design, Liberty University

13 February 2022

“Now a new Bauhaus is founded on American soil. America is the bearer of a new civilization whose task is simultaneously to cultivate and to industrialize a continent. It is the ideal ground on which to work out an educational principle which strives for the closest connection between art, science, and technology.” —László Moholy-Nagy, 1939

László Moholy-Nagy, Heritage Images / Getty Images

Tyranny Displaces the House

Although the greatest art in history was born in the womb of suffering, the years of the Nazi’s tyranny, genocides, and systematic persecution were enough to scare away the minds of creatives. The ideas of modernism were so unwelcome in the Nazi Germany. That led the Bauhaus faculty members leave everything behind and join the flight of intellectuals and artists to America after years of creativity establishing a new school with new rules of modern art and visual communication design.

Gropius and Marcel Breuer moved to teach architecture at Harvard University, and Moholy-Nagy established the New Bauhaus (now the Institute of Design) in Chicago.

Bauhaus with new materials, new techniques

Going back in time to when a restless experimenter who studied law before turning to art replaces Johannes Itten (1888 –1967), the Swiss expressionist painter, designer, and color theorist that taught at the Weimar Bauhaus School of Design, under the direction of German architect Walter Gropius. Meggs wrote:

“A young artist explored painting, photography, film, sculpture, and graphic design. New materials such as acrylic resin and plastic, new techniques such as photomontage and the photogram, and visual means including kinetic motion, light, and transparency were encompassed in his wide-ranging investigations. Young and articulate, Moholy-Nagy had a marked influence on the evolution of Bauhaus instruction and philosophy, and he became Gropius’s “prime minister” at the Bauhaus as the director pushed for a new unity of art and technology.”

Big Apple of Europe

Before The Rise of Nazis and war in Germany, Berlin was the art hub and refuge to creatives and artists. To know the real story to early art life of Moholy, nobody can tell his story better than his daughter, Hattula, a film director, archaeologist speaks on The Moholy-Nagy Foundation website about her father’s art before the Bauhaus, she wrote:

“During the Weimar Republic between the two World Wars, Berlin was the Big Apple for Eastern and Central European artists and writers. The three years Moholy spent in Berlin during his first stay there must have been exhilarating for a young man in his twenties. The most significant development in his art is that it went from being figurative into a short Dadaist phase. And from there it went completely abstract.” She continues: “Moholy was strongly impressed by the Russian Constructivists, who, for a short while, exerted considerable cultural influence in the newly established Soviet Union. Their work was exhibited in a widely-seen show in Berlin in 1922. Moholy embraced this new style with characteristic enthusiasm and energy. The earliest of his Constructivist paintings already illustrate Moholy’s life-long preoccupation with light and transparency, as seen in his signature intersecting and overlapping planes. The earliest paintings are static – they kind of stand and deliver. But by the mid-1920s his compositions had become dynamic and reflect his verve and optimism. He had developed his own individual style.”

Enforcement of the Laws of Modernism

Due to Moholy’s background of law background; discipline, perfection, balance and legibility were top keywords in his vocabulary.

After he served in the WW1, he finished his law studies in Budapest. He was influenced by art of Russian artist Kazimir Malevich. In 1921 he moved to Berlin, where he got exposed to Lissitzky art, and collaborate with De Stijl movement typography and constructivism artists where he fell in love with design.

His obsession with discipline and perfection in art led to his quest to experiment a new level of modern art and visual communication.

Meggs wrote:

“The quest for a pure art of visual relationships that began in the Netherlands and Russia remained a major influence for the visual disciplines throughout the twentieth century. One of the dominant directions in graphic design has beenthe use of geometric construction in organizing the printed page. Malevich and Mondrian used pure line, shape, and color to create a universe of harmoniously ordered, pure relationships. This was seen as a visionary prototype for a new world order. The unification of social and human values, technology, and visual form became a goal for those who strove for a new architecture and graphic design.”

The Law of Typography and absolute clarity

The ideas of Moholy about typography represent his serious relationship with type and graphics in his work style and art decisions. Moholoy’s aesthetics and his principles of typography manifested during the Weimar Bauhaus days contributing with Gropius and the student Herbert Bayer, Meggs wrote:.

“Moholy-Nagy contributed an important statement about typography, describing it as “a tool of communication. It must be communication in its most intense form. The emphasis must be on absolute clarity. . . . Legibility—communication must never be impaired by a priori esthetics. Letters must never be forced into a preconceived framework, for instance a square.” In graphic design, he advocated “an uninhibited use of all linear directions (therefore not only horizontal articulation). We use all typefaces, type sizes, geometric forms, colors, etc. We want to create a new language of typography whose elasticity, variability, and freshness of typographical composition [are] exclusively dictated by the inner law of expression and the optical effect”

Free the Viewers’ Interpretation

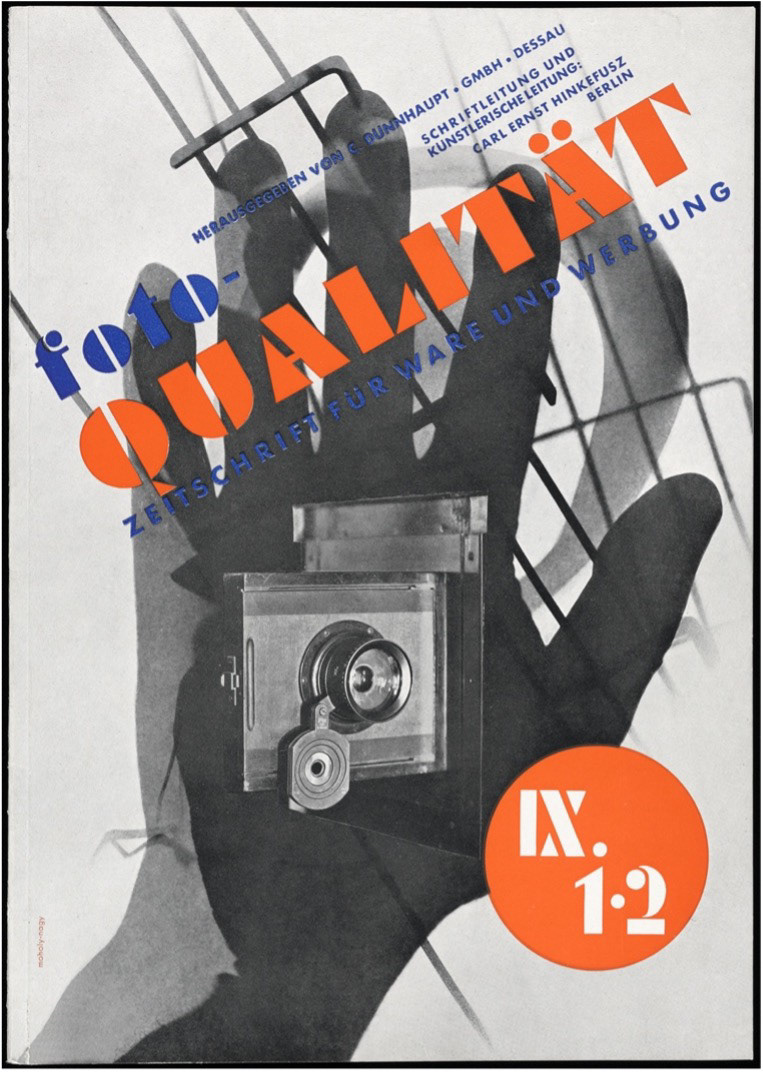

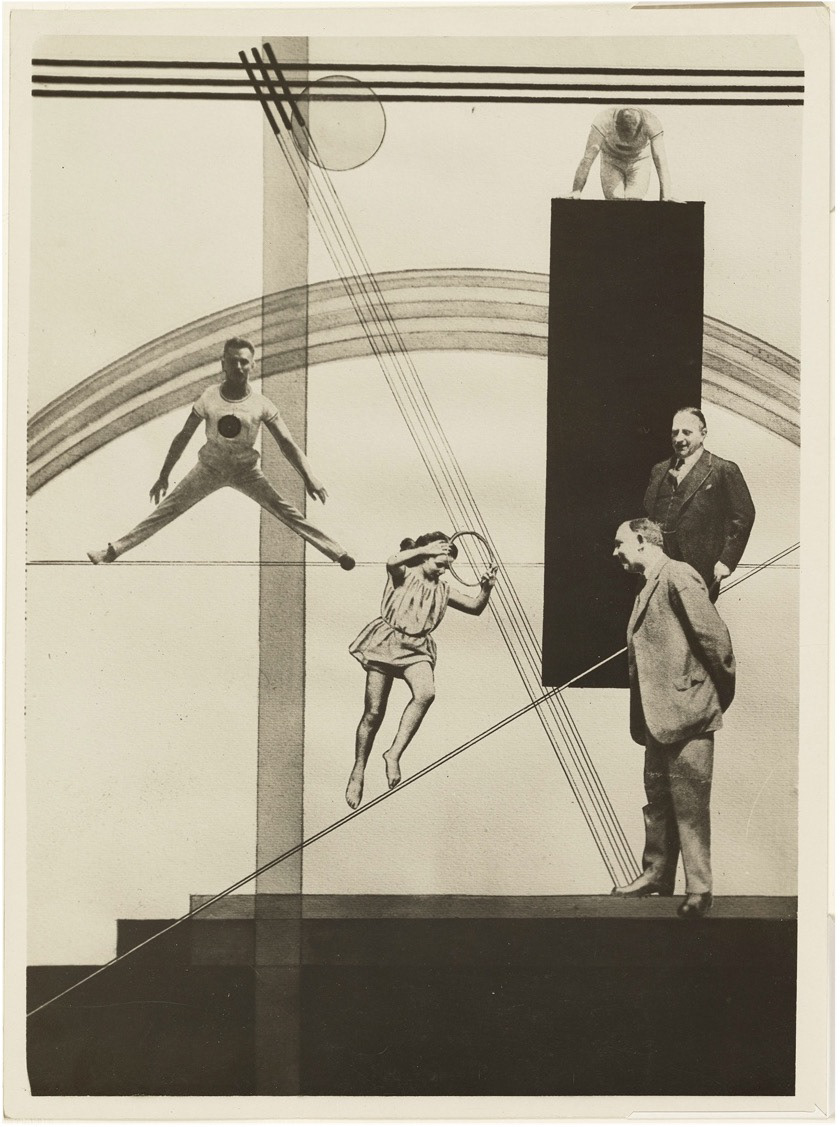

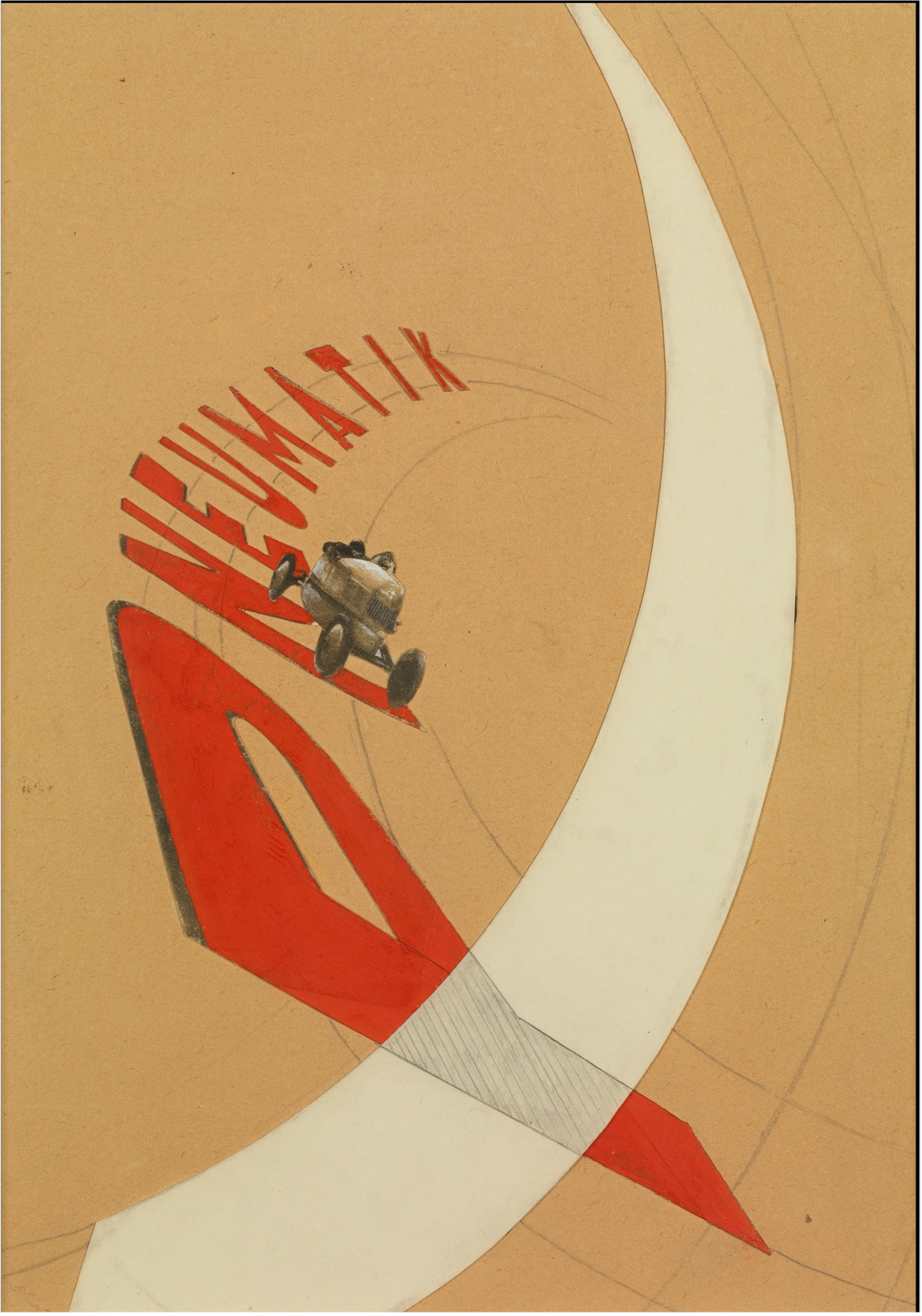

Moholy’s passion for type and photograph inspired the interest and shifted the path that the Bauhaus was taking in visual communications design and married typography and photography and birthed important experiments in both arts. The poster evolved to a typophoto. The objective integration of word and image that communicate a message with immediacy was called “the new visual literature.” Meggs wrote describing the ultimate objective of “Pneumatik” poster and the moments it came to life:

“ Moholy-Nagy’s 1926 “Pneumatik” poster is created with tempera and photo collage. In that year, he wrote that photography’s objective presentation of facts could free the viewer from depending on another person’s interpretation. He saw photography influencing poster design—which demands instantaneous communication—by techniques of enlargement, distortion, dropouts, double exposures, and montage. In typography, he advocated emphatic contrasts and bold use of color. Absolute clarity of communication without preconceived aesthetic notions was stressed.”

The Photograph, a Legal Victory

Using photography in visual communication design adds a flavor of realism to the recipe, the interaction between color, shapes, drawings, and photography that expresses the power of graphic design to reinforce the message communicated to the audience. Moholy was a master in producing outstanding photography using light and dark, using repeated visuals and creative angles, and over painting. This brought the photographs to the frontline as a top priority tool of visual communication, is allowed room of new experiments of photography that inspired generations. Meggs wrote:

“An application of the new language of vision to forms seen in the world characterizes his regular photographic work. Texture, light and dark interplay, and repetition are qualities. In his growing enthusiasm for photography, Moholy-Nagy antagonized the Bauhaus painters by proclaiming the ultimate victory of photography over painting.”

Not Just a Collage

The experiments and techniques of Moholoy in combining his abstract art with photomontage and collage were expressional and original, they were influential and inspiring to whole generations or artists. Meggs wrote:

“ Moholy-Nagy saw his photoplastics not just as the results of a collage technique but as manifestations of a process for arriving at a new expression that could become both more creative and more functional than straightforward imitative photography. Photoplastics could be humorous, visionary, moving, or insightful, and usually had drawn additions, complex associations, and unexpected juxtapositions.”

Work Cited:

Moholy-Nagy, László, Our Bauhaus Heritage, IIT Institute of Design (ID) website,

https://id.iit.edu/new-bauhaus/

Meggs, Philip B, Alston W. Purvis, and Philip B. Meggs. Meggs' History of Graphic Design. , 2006. Print.

Moholy-Nagy, Hattula, The Moholy-Nagy Foundation, Inc.

Wikipedia, Johannes Itten,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johannes_Itten

El Lissitzky, “Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge,” 1919. The Bolshevik 801 army emblem, a red wedge, slashes diagonally into a white sphere signifying Aleksandr Kerensky’s “white” forces. The slogan’s four words are placed to reinforce the dynamic movement. 49 x 69 cm

Alexander Rodchenko, paperback book covers for the Jim Dollar series, 1924. Consistency is achieved through a standardized format; montages illustrate each story. 17 x 12.4 cm

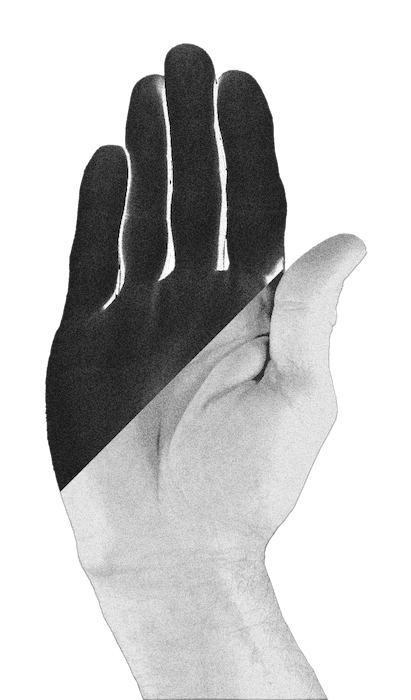

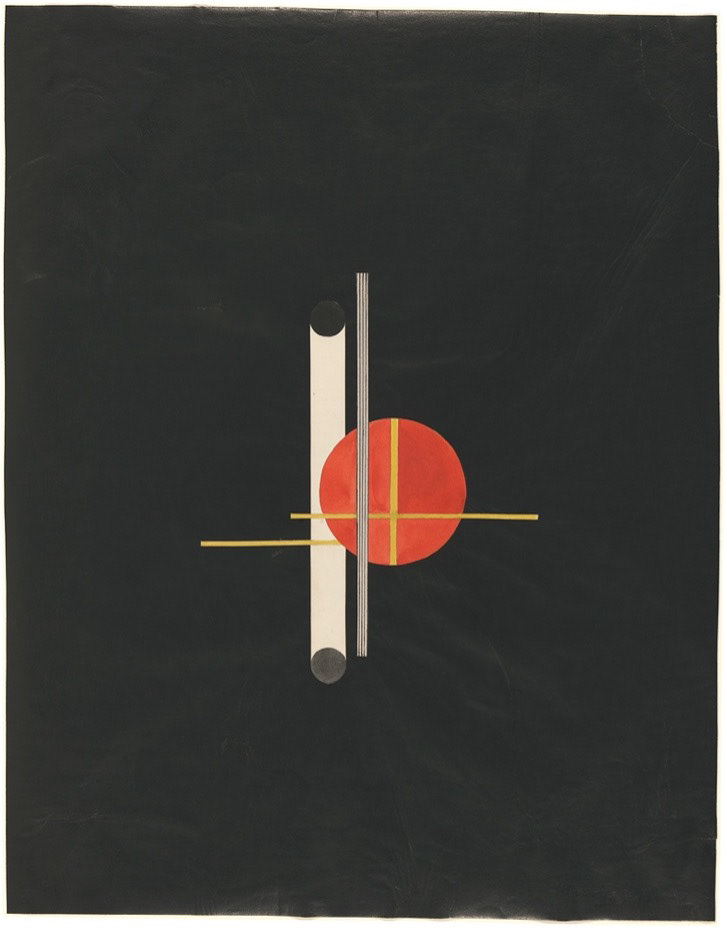

Left: Lazlo Maholy Nagy A Xxi Date Created 1925 Materials Oil On Canvas

Right: Q DATE CREATED 1923 DIMENSIONS 58.9 x 46.3 cm MATERIALS Collage, watercolor, ink, and graphite on paper attached to carbon paper

ABOUT National Gallery of Art, Washington MATERIALS Printed matter

Left: Cover for Foto-Qualität (Photo-Quality) Magazine DATE CREATED 1931 DIMENSIONS 29.7 x 21 cm MATERIALS Printed matter

Right: László Moholy-Nagy, Zirkus und Varietéplakat / Der wohlwollende Herr (Circus and Sideshow Poster / The Benevolent Gentelman) DATE CREATED 1924, DIMENSIONS 28.1 x 20.1 cm MATERIALS Photoplastic (gelatin silver print)

Left: László Moholy-Nagy, Pneumatik: Advertising Poster ( Pneumatik: Reklameplakat ), 1923. Reproduced in Moholy-Nagy, Malerei Fotographie Film , 100. © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Right: László Moholy-Nagy, Love Your Neighbor/ Murder on the Railway 1925 Gelatin Silver Print 14 ¾ x 10 5/8 in Getty Museum